A Brief Overview of Database Indexes

What’s an index?

In simple terms, database indexes are data structures which allow for efficient reading. You can imagine them as lookup tables which store pointers (in most cases) to the location of the searched row in the table.

Hence, if you execute the following query:

1

SELECT * FROM users WHERE user_id = 123456

The database engine will look into the index, locate the user_id (primary key) and use the pointer to access the corresponding row in the USERS table.

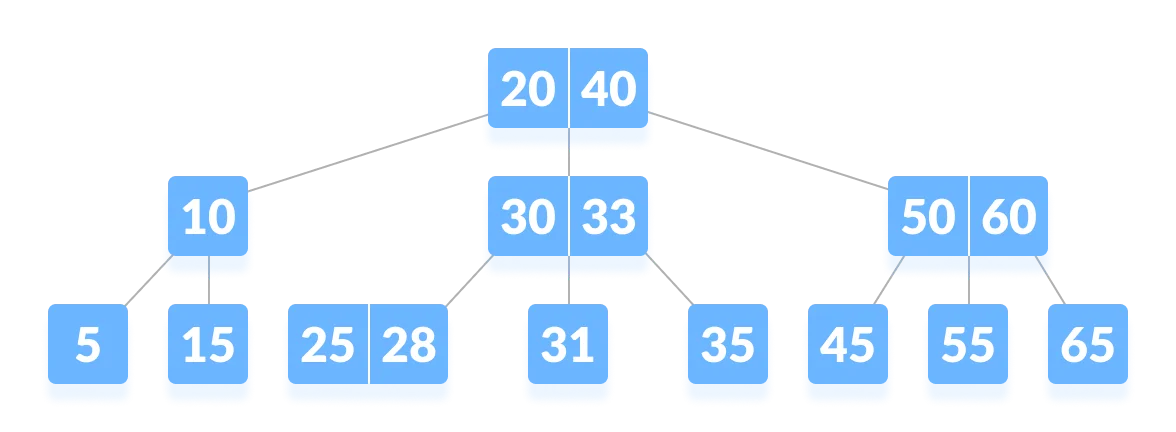

Depending on the type of index used, querying might happen differently in the background. But for the most part indexes require a data structure called B-tree.

B-trees provide sorted data (database records are not guaranteed to be sorted) for easier searching, access and removals.

Why are not all columns indexed?

Aside from the required extra memory, it costs time and processing power to update indexes. For every index on a table, whenever a record is written, an additional write operation to the index table will occur. This can result in prolonged table locking.

Different types of indexes

Some of the most common types of indexes are Clustered index and Non-clustered index, Hash index

Clustered index

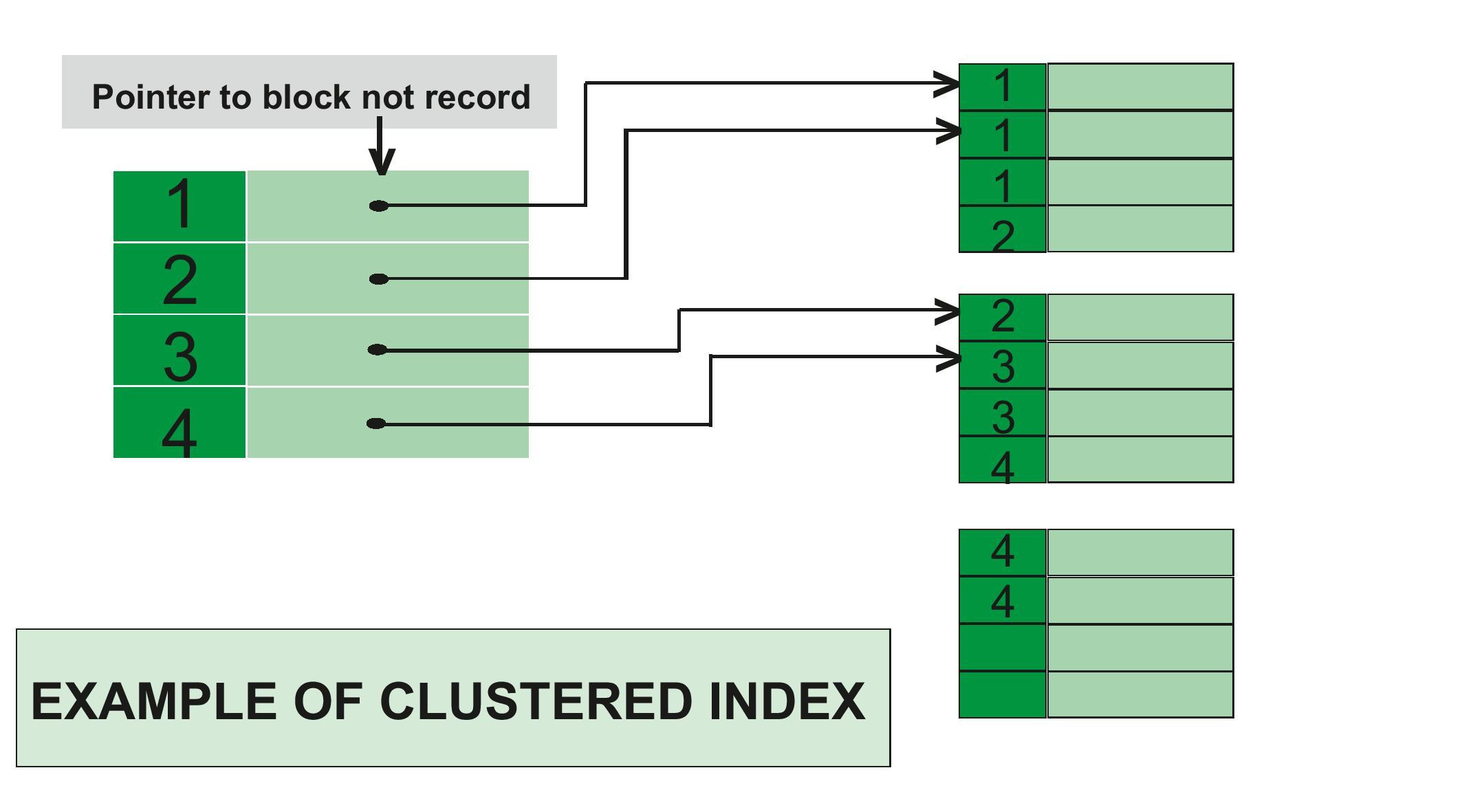

Clustered indexes sort the data rows based on their primary keys and store it accordingly. Therefore, the only way to have a sorted table in any SQL database is by having a clustered index. Behaviour is different between different databases, but there are management systems such Microsoft SQL Server which primary key constraint creates a clustered index by default. What’s so special about clustered indexes is that the data they point to is stored in the same order phisically on the disk as it is in the cluster table.

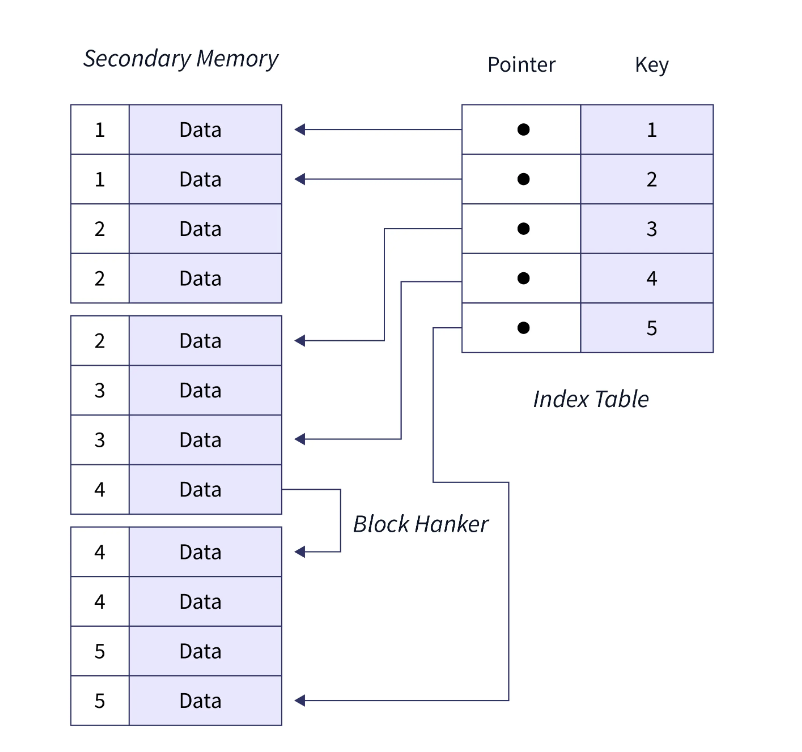

Initially, it can be perplexing to determine the targets of these pointers. To clarify, on the left side, there’s a data structure (usually B-trees) which stores the primary keys of the rows as the keys and the corresponding pointers to physical blocks as values.

Let’s consider that we are searching for the row with PK = 2. We search the clustered table on the left to locate the key 2. Once found, we look up its pointer value, which directly guides us to the physical location where the rows with that key are stored. To be honest, the example above is not ideal, or it is only as good as it can be, given that there isn’t a single example conforming to a proper “algorithm” for selecting pointers to the physical blocks. If you compare this example with the first image on the page, you will notice that the algorithm for pointer selection is somewhat different. Additionally, there appears to be a mistake in the selection of the 5th key’s pointer in the first example. Therefore, it’s advisable not to focus too much on these images but, instead, to remember that clustered indexes are sorted in the same order as the rows are physically stored.

As mentioned earlier, clustered indexes are typically employed for primary keys. Can they be used for any other field? The possibility exists, but let’s examine the scenario with the following data:

user_id name

1 Alex Anderson

2 Mike Peterson

3 Sarah Mitchell

4 Emily Turner

If you designate name as a clustered index, depending on the sorting algorithm, you could incur significant costs due to physically shifting/moving a substantial amount of data. If the cluster is created on the name column, the rows of the table are stored physically in ascending or descending order of name.

Non-clustered index

Non-clustered indexes are not dependant on the physical order of the data. They’re built using the same B-tree structure used for clustered indexes, but with the difference that the data and the index are stored separately. A non-clustered index contains a pointer, but rather pointing to a physical location of where the records with this PK lie, they point directly to the data row.

So, what’s the purpose of non-clustered indexes? Their goal is to improve the performance of frequently used queries not covered by the clustered index, if there’s one at all. An important note; tables with a clustered index are called cluter tables and tables without one are called heaps.

Heaps

Heaps are tables which store their information in pages and are unordered. Rows are identified by a single 8-byte row identifier (size might differ between databases). The heap table is characterized by a single IAM page (Index Allocation Map) which holds together a heap, a collection of pages.

Row locators

At this point, we’ve discussed row locators several times - these are pointers from index rows in a non-clustered index to corresponding data rows. In the case of a clustered table, the row locator serves as a pointer to the physical block section where the records associated with the key can be found.

Included columns in the index?

You may benefit from including certain columns to your non-clustered indexes if you regularly have to query them.

| ID | RID | Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0x1A2B3C4D5E6F7A8B | Tony |

| 2 | 0x4E7A8F1D2B6C3E9A | Sony |

Let’s say your query requires you to retrieve a user’s name using their primary key. To avoid inefficient data access, you may include the name column within the index and directly return the information.

Yes, data access is costly. Retrieving data directly from an index is consistently more efficient compared to querying the index, then accessing the record and finally returning the data.

However, these types of indexes are only beneficial when you frequently run specific queries. Otherwise, they may allocate unnecessary memory without providing significant advantages.

Comparison of clustered and non-clustered indexes

This is a really nice table I found on GFG:

| Feature | Clustered Index | Non-Clustered Index |

|---|---|---|

| Speed | Faster | Slower |

| Memory Usage | Requires less memory for operations | Requires more memory for operations |

| Data Storage | Main data is in the clustered index | Index is a copy of data in a non-clustered index |

| Number of Indexes Allowed | Only one per table | Multiple per table |

| Disk Storage | Stores data on disk | Does not inherently store data on disk |

| Storage of Data in Index | Stores pointers to blocks, not data | Stores both value and a pointer to the actual row |

| Leaf Nodes | Actual data in leaf nodes | Leaf nodes do not contain actual data, only included columns |

| Order of Data | Clustered key defines order within the table | Index key defines order within the index |

| Physical Order on Disk | Physically reordered to match the index | Logical order does not necessarily match the physical order |

| Size | Large (especially for the primary clustered index) | Comparatively smaller, especially for the non-clustered index |

| Default for Primary Keys | Primary keys are default clustered indexes | Composite keys with unique constraints act as non-clustered |

Hash index

Hashing indexes enable rapid access with nearly constant time complexity, typically O(1). This involves a conventional hash table where keys are rehashed as 4-byte hashes, and the corresponding pointers to record rows. Generally, hashing indexes demonstrate efficiency until they encounter a significant number of collisions. In such cases, collisions—instances where different keys produce the same hash—can impact the performance of the hash index, emphasizing the need for careful consideration in design and implementation.

An illustrative instance of a hash index is associating a primary key (PK) with a password hash to avoid binary searching for the corresponding data entry.